-

Our current ‘In Focus’ shines a spotlight on the life and work of Coral Woodbury giving the reader an enhanced overview of the artist, her general working practice, and an interview with Coral accompanied by images from different bodies of work and links to interviews and articles.

Coral Woodbury was born in New York in 1971 and currently lives and works near Boston. She has a Bachelor of Fine Arts, in painting and printmaking and spent a semester studying in Italy. Following her Masters in Museum Studies, she worked as a museum curator at the Newport Mansions documenting the untold stories of the domestic service.

Coral critically reinterprets Western artistic heritage from a feminist perspective, bringing overdue focus and reverence to the long line of women artists who worked without recognition or enduring respect.

-

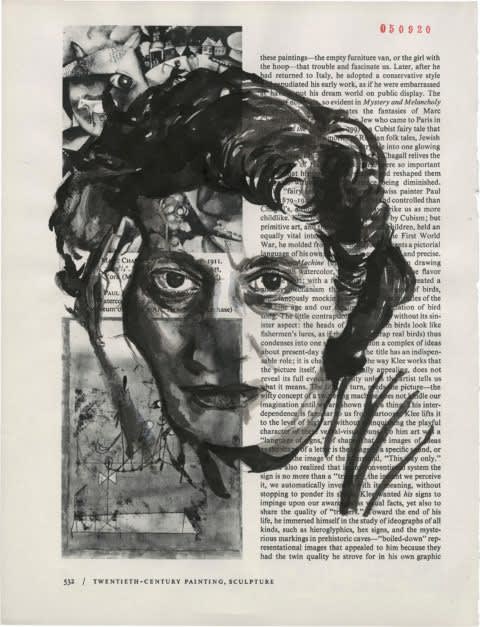

Coral’s most recent and ongoing project Revised Edition rectifies the complete erasure of women artists from the first 29 printings of Janson’s History of Art. First published in 1962, Janson’s became the defining art history text of the twentieth century, shaping the Western canon and understanding of art for generations. And yet the text did not mention a single female artist until 1986. With Revised Edition, Coral inks portraits of women artists on pages torn from the book, making visible those who have been obscured, reclaiming space for them.

Coral has participated in numerous residencies including in Italy with rosenclaire, with whom she has worked for nearly 30 years. In 2020 she was a finalist for the international Mother Art Prize, awarded by Procreate Project and exhibited at Cromwell Place, London, UK. In 2018 she was awarded the MA Juror’s Prize for Painting at the Boston Biennial V, Atlantic Works Gallery, Boston.

-

What has even been deemed art at all, all of art history, was defined and determined by men. Women’s art was demoted to domestic decorative craft. Recognising women from previous ages also means recognising the very exceptional and rare who managed to be artists despite all the opposing forces, and to come down through history

-

-

Q&A between HackelBury Fine Art and Coral Woodbury

HackelBury Fine Art: In your work at the Newport mansions you talked about wanting to make the ‘invisible visible’. Was this part of the motivation behind the focus on women artists in your ongoing project Revised Edition?

Coral Woodbury: The Newport Mansions work was about telling the story of domestic service, which was largely women. But Revised Edition came about because I was at a point in my work when I was wondering how to move forward, what my work needed, what direction to take it. What have other women, mothers, done as artists? I realised I didn’t really know, because I hadn’t been taught about any. When I started considering my dearth of knowledge about women artists, I realised it was endemic to the way art history was taught. I went and looked and there were no women in the textbooks. None. Janson’s History of Art, the canonical text book of 21st century art history in Western culture, had completely left them out. This was a type of active repression. As women gained more rights, they were erased from history.

HBFA: How do you choose the individuals whom you draw in Revised Edition? It must be like the work of an archaeologist… uncovering layers?

CW: It is immense — which is wonderful — there are so many artists! I am still mostly working within the Western canon, but there are so many other cultures and countries with their hidden histories of women making art. As much as I look for diversity and other sources of information, I am still limited in the scope of what I will be able to accomplish. But I won’t run out.

-

HBFA: I imagine it has to be an organic process where one thing leads to another?

CW: It is intuitive, fluid and driven by serendipity and curiosity. I ask myself ‘Who am I learning about’? And then, ‘Who am I not?’

HBFA: Of the women you have chosen to represent, are there many mothers? Is there a pattern there?

CW: I want to know who these women were, what their lives were like and how their work connects to their biographies. The mothers among them, unsurprisingly, responded quite individually. Some essentially left their children, some worked with children underfoot. Some died in childbirth.

HBFA: Have you chosen art as a vehicle for activism?

CW: It is a form of activism but the art came first. I always wanted to be an artist. There is an early photo of me in a high chair with a cheap watercolour set, absolutely enthralled.

HBFA: What made you choose to draw the portraits and not to paint them? Also what materials do you use for the drawings?

CW: I use sumi ink and brush, though my favourite drawing implement is a stick. It is a grapevine from when I worked as a grape harvester in Italy. It curves to my hand and is worn smooth. If my house was burning down that would be one of the first things to grab.

HBFA: Why did you choose to use only black ink?

CW: I wanted the artists to meld with the pages of the book. Colour would sit on top of the page in a different way, and I wanted them to blend with what is already on the page. Ink was the right medium, the same as that of the book. The women needed to be in, to be part of the book, and the history it tells. But there is another reason, and that is to express the common humanity and shared struggles among women. I wanted to show unity among heterogeneity.

HBFA: How has your academic background impacted your work? You talk about the materiality of what you are doing. The sense of object? Can you expand?

CW: Working in museums meant I could be with art, study and be inspired by it. But there was another thread to it as well — I have always loved the material culture of previous generations. My great grandmother had a little antique shop in the front parlour of her house. I grew up with the remnants of that shop all around me. My grandmother’s attic was a trove of mysterious old objects, and as a kid I would spend my allowance on old things at yard sales. Those objects are a direct connection to other people and other times. These remainders have stories to tell if we can unlock them. My work explores that in many different ways.

I’ve started making paintings of material culture which belonged to women artists. Looking at tiny details from photos, like Cassatt’s teapot, Kahlo’s earring or Krasner’s paint dappled boots. These are objects which give a glimpse of that person — details which are overlooked. There is something intimate about these objects. So much of material culture was from the domestic sphere, and things made by women’s hands but relegated to decorative arts.

-

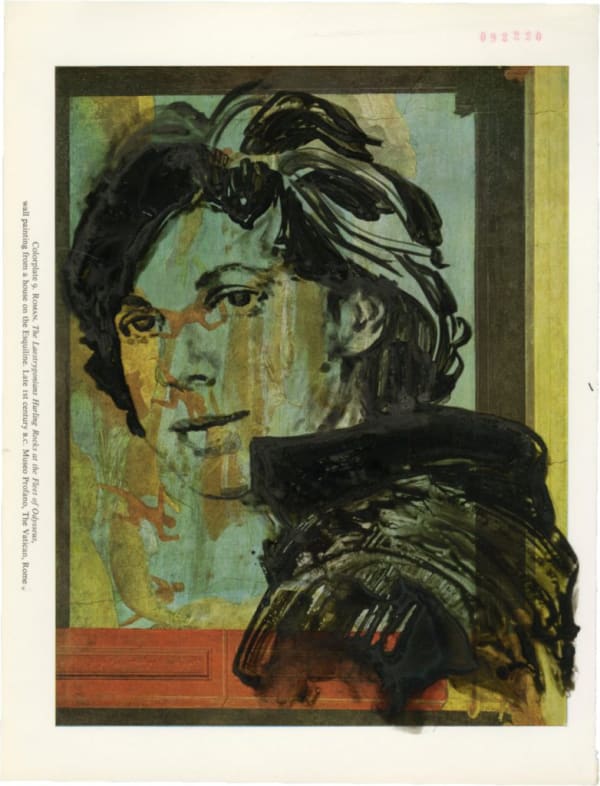

HBFA: Will you talk about the Himalaya and Havana Colour series?

CW: Both were trips I made because of my work. I participated in #00Bienal in Havana. Not the official biennial but an unofficial, and therefore, unsanctioned one. Some international artists were turned back at customs, but I was an unknown. I also had an exhibition in a museum in Kathmandu, and was welcomed into a group of artists. Travelling with art provides a way of being embedded in a community. You come into shared proximity with people and their daily lives. I wanted to find a way to document those trips and experiences. I made it a project, when I land in a new country, to find an old book resonant of that place. I have worked a lot with palimpsests and this is an enduring influence. I use a tiny palette of gouache, and the book I find as a painting pad or sketchbook. It is a way of record-keeping and communicating. I don’t speak Spanish or Nepalese, but art is universal and people are curious. I choose colours that I see around me, and capture them as faithfully as I can. Each place has very distinct colours, a language in colours, which I do speak.In Nepal I found an old book on yoga, falling apart, with no binding and full of bookworm holes. I made my colour studies in the simplified composition of a mandala. In Cuba I found a book about music. As I became more aware of the censorship and harassment my new artist friends endured, I started covering over the musicians in the book, silencing them. They became blindfolded and muted by my blocks of tropical colour. These books become a visual journal. In Cuba, a growing awareness of the repression struck me. I had taken so much for granted, even my right to make art, until I visited a country where that right depends on loyalty to state ideology.

HBFA: Where does your love of books come from? Why are you an artist and not a writer?

CW: I have always loved to read, to journey as someone else, to somewhere else. There was no library in my town; the school library was it for me. I would bring bags of books home from school for the summer holidays — but I never wanted to be a writer. I did do a lot writing for academic papers when I worked in museums and wrote tours for the Newport Mansions, but that wasn’t about my voice. I was interested in how to tell other people’s stories — which it seems is what I am still doing.

HBFA: Does the text in the books you use become your canvas?

CW: Exactly. It becomes a composition to work within — its lights and darks, its linear qualities and texture, and the added depth of content.

HBFA: Your books are chosen with a deliberate thought process and the subject matter is clearly very important….

CW: Books offer a tension between text and image. I became fascinated with palimpsests. These are ancient parchment manuscripts that were scraped down and overwritten, basically recycled because of the expense and labour of obtaining new pages. But the ink is embedded in the original vellum and over years the original text re-emerges. You get a double layer of languages and meanings that all come together in a story told across millennia. This object connects humans across vast expanses of time through their thoughts and their hands.

HBFA: Is there a historical fluidity?

CW: There is a sense of fragility and endurance at the same time. Both a transience and a memory.

HBFA: In the Palimpsest series you paint oil on linen and there seem to be certain themes which appear. Titles such as ‘Broken Spine’, ‘Bandage’ and using materials, such as turmeric, which have renowned healing qualities. Can you explain?

CW: I broke my neck and spent 6 months in a neck brace, and required surgery which took some hip bone and put it in my neck, and fused my vertebrae. It was a terrible time.

HBFA: How did this life-changing event affect your work?

CW: There are parallels between book and body, the spine that binds it and holds it together. The vellum and the skin. What is held inside, and the covering. The sense of meanings and story. Book is a metaphor. Its broken spine means it will fall apart. Breaking my neck made me really ill. My immune system collapsed. I had three kids — I was not making art at the time. That all coincided with witnessing the sudden, awful, death of someone close to me. The kind of loss that makes you re-evaluate. How much time are we here for? What do we want to do with our short time? While those things were traumatic, what they gave me is so much greater than what they took away. Human life doesn’t come without suffering. I began thinking a lot about healing and what my work meant. Those experiences gave me back my work, it became an imperative. The way I grieved was starting to paint again.

HBFA: Tell me about your interest in Kintsugi.

CW: Kintsugi is about the beauty of something that has been broken and repaired. The work of healing is what led me to discover it. As humans, it is not our perfection that makes us, but the broken places which we have tended and which allow us to grow. Some of the Broken Spine paintings have gold leaf in the centre crack. Patching with gold is a way of honouring and cherishing those broken places and making them precious.

HBFA: You seem to be driven by a strong social conscience. Was that part of your upbringing or was there an event in your life that became the catalyst for this?

CW: Being the oldest in a pretty chaotic, unstable, and frankly, turbulent, family dynamic, and becoming aware at a young age (through my parents adopting four children from India and Korea) of the plight of other children around the world, must have had an impact on my sense of responsibility. But as a kid I also remember feeling pretty helpless about it. Of course, I was. As an adult, that sense of my smallness in the face of all that is enormously and globally wrong and imperilled remained. Until that experience of coming up against mortality, mine and another’s. That, conversely, vivified me. I thought that if art could comfort and restore me, it could others. I spent the next several years making art with the homeless and addicted populations. While any individual effort of social justice or environmentalism can still feel futile, I figured out that art is the tool I have.

HBFA: What was your career path?

CW: It was a bit roundabout. An art degree, the challenge of making a living, a museum studies Masters degree, engaging work, raising children, and back around to painting. Art school was not deemed practical enough, so I attended a liberal arts college — but stubbornly pursued a Bachelor of Fine Arts in Painting and Printmaking. Blind luck, or blessed fate, landed me for a semester in Florence, where I learned to paint, and why to paint, from rosenclaire, an artist and teacher duo. They have remained my mentors ever since, even across years I was barely making art. In a recent virtual residency they led, there were 48 of us from 10 countries. This group has now worked together for 30 years. I’m not sure there is anything like it in the art world now.

HBFA: I have been thinking about women in Renaissance paintings (something you have touched on in your work). There are many interesting women featured in Renaissance art. Has the exposure you had to Florence — the birthplace of the Renaissance — had an impact on your work?

CW: My favourites were the Ghirlandaio frescoes at Santa Maria Novella, especially the Life of Mary. I love the women in those. I would stop on my way to school and just sit in the Tournabuoni chapel, gazing up at them. I was just reading about the Loggia dei Lanzi and an art historian pointed out how the earlier sculptures presented images of the power of women. But Judith slaying Holofernes was shortly replaced with an image of male dominance. I am working on a collage to restore Judith to a 19th century photo I have of the Loggia. And I am working on a big painting now, based on Bellini’s Madonna and Child with Two Saints, in Venice’s Accademia. A ‘Sacra Conversazione’ (Sacred Conversation). In it I replace Mary and the Saints with three first generation abstract artists. These works take art historical images and recreate them to maintain that story but also tell a different kind of story with new protagonists. A different kind of palimpsest.

-

Coral Woodbury In Conversation with Beth Greenacre

-

HBFA: What have been the key milestones in your life and has your work shifted over the course of your career?

CW: The thing that made art possible, inevitable, for me was finding teachers when I was young, far away in Florence, and their sustaining mentorship for thirty years. Even with busy years going by, the network of artists and rosenclaire were always out there. My life experiences of loss, and those of abundance — motherhood. Mothering three children, one with autism. But this eternal drive to work as an artist, to draw and paint, that is the road between milestones.

HBFA: What research and planning goes into each body of work. How important is process versus product?

CW: Research happens simultaneously as each body of work is in itself a form of research. One does not precede the other.

HBFA: What are the key influences in your life and what inspires you as an artist?

CW: There isn’t any one artist who has been a particular inspiration – what I have found through doing Revised Edition is that I am looking to so many women artists. All of them have endured repression and vaulted barriers to be true to their purpose and their work. I have done over 100portraits so far and have lists of many more, and all of them in one way or another struggled because they were women artists.

HBFA: Do you have a favourite museum or gallery close to home?

CW: I love the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum — one remarkable woman’s incredible collection, in the home she built. It gives a sense of how she lived and how she thought. Her will stipulated tha nothing in the galleries be changed, and so there is that magic of walking back in time. And it is built like a Venetian palace, with a courtyard, so it is a little piece of Italy for me.

HBFA: Do you have a daily routine or ritual that helps you find structure in your day and your work?

CW: I learnt this over the past month, as I have been so busy with a solo show, drawing residency, and making new work for the Newport Art Museum. I couldn’t keep up with my routine with Revised Edition and realised how much I felt ungrounded without it. I realise how stabilising and centring it is for me. When I start each morning with ink and brush, if I’ve done a portrait before 10 am, then I have already done something that matters. At night I try to draw up the ink for the next morning, choosing the artist and finding an image to work with. I look for an image where the artist is looking out and making- direct eye contact. It makes a connection with the viewer but there is also something defiant about it when you see them all together, looking at you. But for me, in the process of drawing, that eye contact is important, making that connection with that person. I start every morning with meditation and gratitude practice. I am a very orderly person. My studio is clean and ordered — my palette and brushes are cleaned and put away each day. I cannot work in a chaotic environment.

HBFA: In what way has the last year and half with the pandemic affected you as a person and as an artist?

CW: I feel guilty, but the past year has been good to me. There has been so much crisis and suffering, but for me it has been a blessing. I loved having my kids home. Numerous opportunities for my work arose and I am now working with two galleries, so I feel blessed. What happened this past year made me realise how much is unessential. I am really an introvert and love the quiet. I live at the border of a state forest, so I spend a lot of time in the woods and observe what is changing with the day, the season, the light. I appreciate the quiet time to think about the way I want to live in the world and to re-evaluate what is invaluable. And it has given me time to focus on my work. Above all I am so grateful my family has managed to stay healthy, and for the privileges that kept us safer. There should not be such privileges, and the disparities are glaring.

-

CORAL WOODBURY

Broken Spine IV, 2021oil, ashes, and gold leaf on linen

Art size: 40.6 x 51 cm / 16 x 20 inches

In Focus: Coral Woodbury

Current viewing_room